Balancing bacterial concerns with scalding concerns in your hot water delivery system

When it comes to choosing the temperature setting on a water heater, there are two opposing aspects that require consideration. If the temperature selected is too low, we risk cultivating an ideal environment for Legionella bacteria to grow and multiply. However, setting the temperature high enough so as to kill harmful bacteria will present a significant scald risk to home occupants. Let's delve into this quandary in more detail, and discuss what we can do to effectively manage these competing risks.

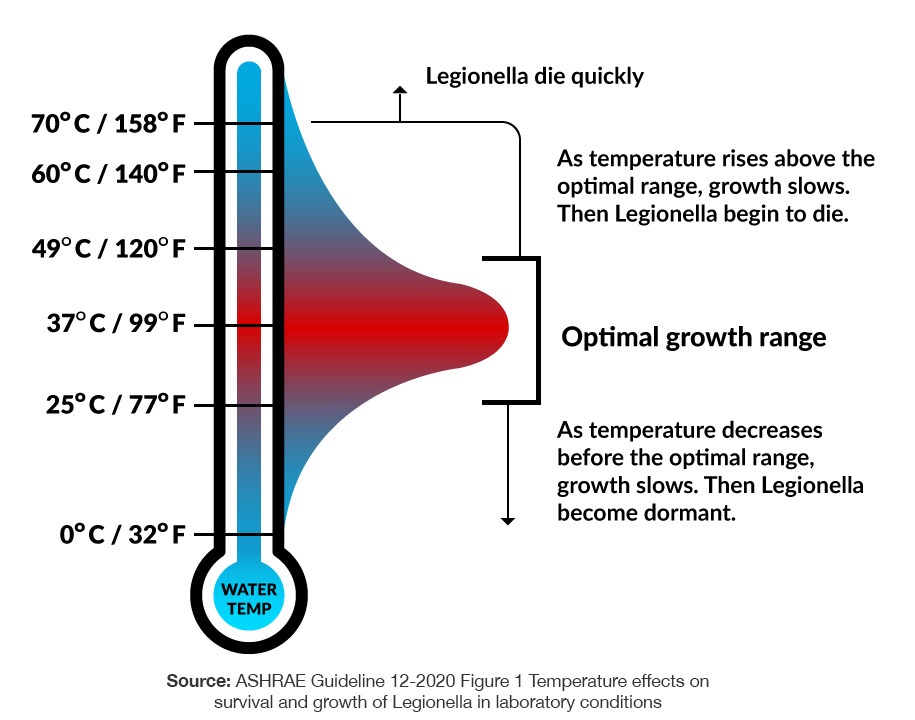

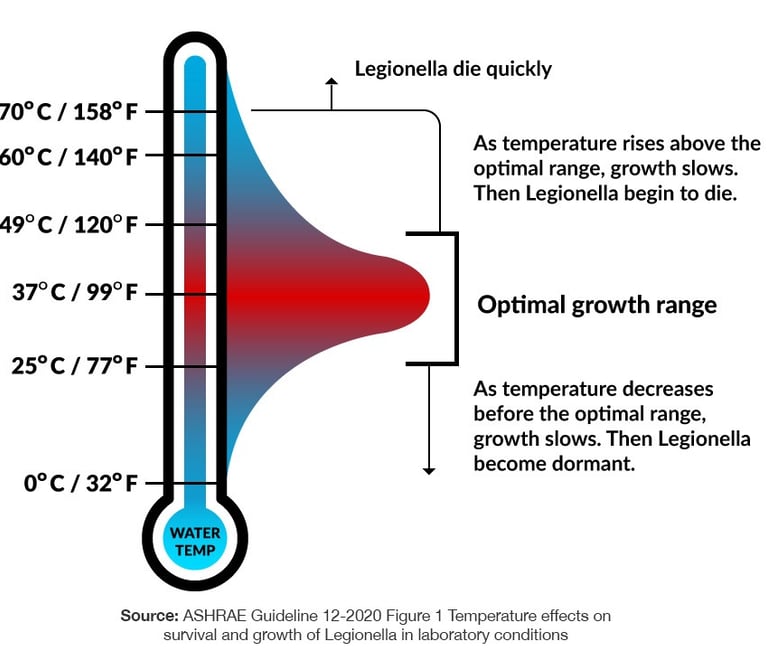

First, a little bit on Legionella bacteria. Legionella bacteria was first discovered in 1976 after 182 attendees of the Pennsylvania State American Legion conference at the Bellevue Stratford hotel in Philadelphia fell seriously ill. Ultimately, 29 individuals would die due to the mysterious pneumonia-like affliction that would later be named Legionnaires' disease. Both the name of the newly discovered bacteria and the associated affliction were named to recognize the American Legion attendees that were affected. The cause of the first documented Legionnaires' disease outbreak was determined to be due to contaminated aerosolized water produced by cooling towers in the hotel HVAC system. Legionella thrives and multiplies in stagnant water somewhere between 77° and 113°. Below 68° it becomes dormant, and at 140° 90% of the bacteria is killed in two minutes.

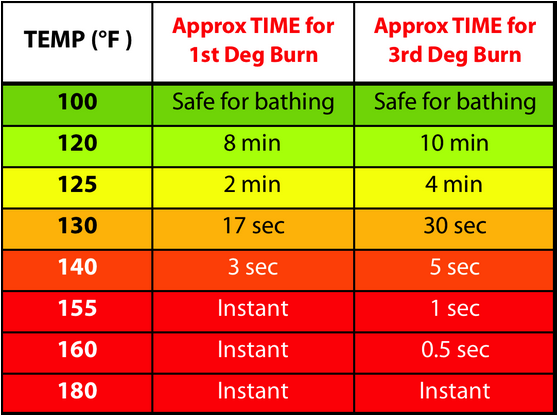

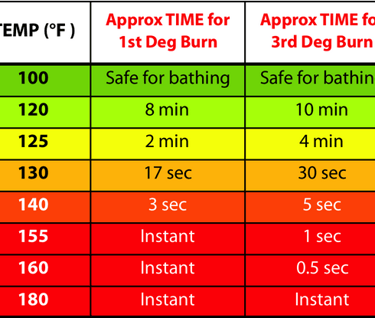

So, just set your water heater to 140° to kill any bacteria and life is good? No, of course not. Building codes generally prescribe a maximum water temperature coming out of a shower/tub fixture to be no greater than 120°. Codes have not yet prescribed the same requirements for private residence kitchen or lavatory sinks etc. This is probably due to the belief that scalding within a shower is more dangerous and harder to avoid compared to scalding at a sink, though scalding at a sink can certainly still occur, especially for children or the elderly.

Modern shower/tub fixtures are made to protect against scalding and thermal shock. Thermal shock is the sudden change in temperature that can result in a person, especially the elderly, scrambling to avoid the new water temperature and may result in a fall leading to serious injury. If you grew up in an older home, you probably have experienced this situation when someone flushed a toilet, which causes a drop in cold water pressure leaving only hot water coming out of the shower fixture. Modern shower/tub fixtures are equipped with either a pressure balancing valve or a thermostatic valve to compensate for the sudden drop in either hot or cold water pressure for the purposes of protecting against thermal shock. I won't go into the difference between the two types of valves here other than to say that thermostatic valves are the more advanced and more expensive option. If you have a shower that has two separate levers, one for the temperature and one for the flow rate, you most certainly have a thermostatic fixture. In addition to the ability to compensate for pressure changes, all modern shower/tub fixtures will have a limit-stop mechanism that limits the temperature that comes out of the fixture. Below is an example from a pressure balanced type valve fixture. The outer plastic component can be adjusted to limit the temperature by pulling it out and re-inserting it into the inner component further to the right. The inner and out plastic pieces have small gear-like teeth. In a pressure balanced valve, you may need to re-adjust the limit stop seasonally to account for differing cold water input temperature or anytime you change the temperature setting on your water heater. One of the additional benefits to a thermostatic valve is that it will maintain a consistent temperature regardless of these changing variables.

So, modern code requirements already help to protect against scalding in the shower/tub, but what if we want to maintain water temperature high enough inhibit bacterial growth, but also limit the risk of scalding? Do we have any options? Yes, we can achieve both outcomes by installing either point of use thermostatic mixing valves which would tie into the plumbing at each fixture or installing a master thermostatic mixing valve at the water heater. In either case, cold water would be mixed with hot water needed to inhibit the growth of Legionella bacteria, let's say 140°, to bring the temperature down to 120° or less at the fixture. The use of these mixing valves also have the added benefit of safely increasing the amount of hot water available since a smaller amount of 140° water mixed with cold water is needed compared to hot water set at a lower temperature.

In summary, without the use of mixing valves described in the article, the final determination of what temperature to set your water heater at will depend on a number of factors such as whether there will be small children in the home, whether occupants or visitors have an auto immune deficiency, whether occupants visitors are eldery etc. etc. However, I would recommend 125° to be around the temperature that I would target in most instances without the use of additional mixing valves for occupants of relatively good health. Keep in mind though, that a traditional water heater set at any given temperature will vary in actual temperature due to stratification within the tank among other factors.

Finally, below is a good supplemental video from the UK on the topic. He argues that instances of Legionnaires' disease in a residential setting is not as common as in a commercial setting due in part because water in a residential setting typically does not have the chance to become stagnant. I tend to agree with his premise. However, given the right environment for growth, Legionella could be problematic in any setting, and the risk you are willing to take likely has a lot to do with whether the occupants have additional risk factors that would make them more susceptible to Legionnaires' disease, or you know that your water has a greater potential for stagnation. For example, in a vacation home where the water may not be used for long stretches of time.

That's all, until next time!